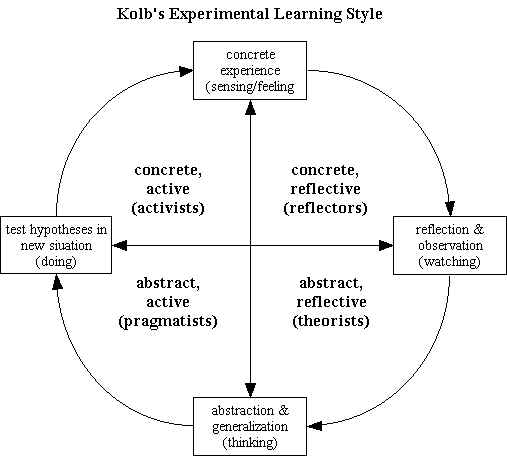

Kolb's Experiential Learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (1984) theorized that people develop preferences for different learning styles in the same way that they develop any other sort of style, i.e. - management, leadership, negotiating etc. To understand the value of the learning inventory, learners must first have a basic understanding of the experiential learning model and know what their preferred learning style is. This model provides a framework for identifying students' learning style preferences.

David Kolb (1984) found that the four combinations of perceiving and processing determine the four learning styles. According to Kolb, the learning cycle involves four processes that must be present for learning to occur:

Activist - Active Experimentation (simulations, case study, homework).

What's new? I'm game for anything. Training approach - Problem solving,

small group discussions, peer feedback, and homework all helpful; trainer

should be a model of a professional, leaving the learner to determine her

own criteria for relevance of materials.

| Reflector - Reflective Observation (logs, journals, brainstorming). I'd

like time to think about this. Training approach - Lectures are helpful;

trainer should provide expert interpretation (taskmaster/guide); judge

performance by external criteria.

| Theorist - Abstract Conceptualization (lecture, papers, analogies). How

does this relate to that? Training approach - Case studies, theory readings

and thinking alone helps; almost everything else, including talking with

experts, is not helpful.

| Pragmatist - Concrete Experience (laboratories, field work, observations).

How can I apply this in practice? Training approach - Peer feedback is

helpful; activities should apply skills; trainer is coach/helper for a

self-directed autonomous learner.

|

|

![]()

The Learning Organization Home Training & Induction

"...Most top-down change strategies are doomed from the start. Driving change from the top is like a gardener standing over his plants and telling them to grow harder. A good gardener addresses the balancing processes, making sure there is enough water and nutrients. Likewise, leaders should focus less on change itself and more on planning for the natural reactions against it. If people do something new that is effective, they will want to do more of it." - Peter Senge

In 1990, Peter Senge popularized the "Learning Organization" in The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization . He describes the organization as an organism with the capacity to enhance its capabilities and shape its own future. A learning organization is any organization (e.g. school, business, government agency) that understands itself as a complex, organic system that has a vision and purpose. It uses feedback systems and alignment mechanisms to achieve its goals. It values teams and leadership throughout the ranks.

He followed that book with 1999's The Dance of Change: The Challenge to Sustaining Momentum in Learning Organizations which shows the difficulty of achieving the learning organization.

The five disciplines are:

![]()

Knowledge Management Home Training & Induction

"...for thousands of years, humans have been discussing the meaning of knowledge, what it is to know something, and how people can generate and share new knowledge." - Knowledge Management Tools, Rudy L. Ruggles, III, 1997

Simply put, knowledge management is about capturing knowledge gained by individuals and spreading it to others in the organization. Its purpose is to help us manage it better.

Although a number of management theorists have contributed to the evolution of knowledge management, among them such notables as Peter Drucker, Paul Strassmann, and Peter Senge; Ikujiro Nonaka makes knowledge management an official discipline when he is appointed as the first distinguished professor of knowledge at the University of California in 1997.Knowledge management can be viewed from two perspectives:

Knowledge can be viewed as "Knowledge = Object" which relies

upon concepts from "Information Theory" in the understanding of

knowledge. These researchers and practitioners are normally involved in the

construction of information management systems, AI, reengineering, etc. This

group builds knowledge systems, while the next group changes the way we use

knowledge, which ultimately changes human behavior.

| Knowledge can be viewed as "Knowledge = Process" which relies

upon the concepts from philosophy, psychology, and sociology. These

researchers and practitioners are normally involved in education,

philosophy, psychology, sociology, etc. and are primarily involved in

assessing, changing and improving human individual skills and behavior. | |

With knowledge management, the unmeasurable must be measured. "Every organization — not just businesses — needs one core competence: innovation. And every organization needs a way to record and appraise its innovative performance."—(Peter F. Drucker, Harvard Business Review 1995)

There are two kinds of knowledge:

Explicit knowledge - It can be expressed in words and numbers and shared

in the form of data, scientific formulae, product specifications, manuals,

universal principles, etc. This kind of knowledge can be readily transmitted

across individuals formally and systematically. also, it can easily be

processed by a computer, transmitted electronically, or stored in databases.

| Tacit knowledge - This is highly personal and hard to formalize, thus

making it difficult to communicate or share with others. Subjective

insights, intuitions and hunches fall into this category of knowledge.

Furthermore, tacit knowledge is deeply rooted in each individuals' actions

and experiences, as well as in the ideals, values, and emotions that they

embrace. The subjective and intuitive nature of tacit knowledge makes it

difficult to process or transmit the acquired knowledge in any systematic or

logical manner. For tacit knowledge to be communicated, it must be converted

into words, models, or numbers that anyone can understand. Also, there are

two types of tacit knowledge:

|

|

The most valuable employees often have the greatest disdain for knowledge

management. Curators badger these employees to enter what they know into the

system, even though few people will ever use the information.

| The managers of these systems know a lot about technology, but little

about how people actually use knowledge on the job.

| Tacit knowledge is extremely difficult to capture into these systems, yet

it is more critical to task performance than explicit knowledge.

| Knowledge is of little use unless it is turned into products, services,

innovations, or process improvements. | |

![]()